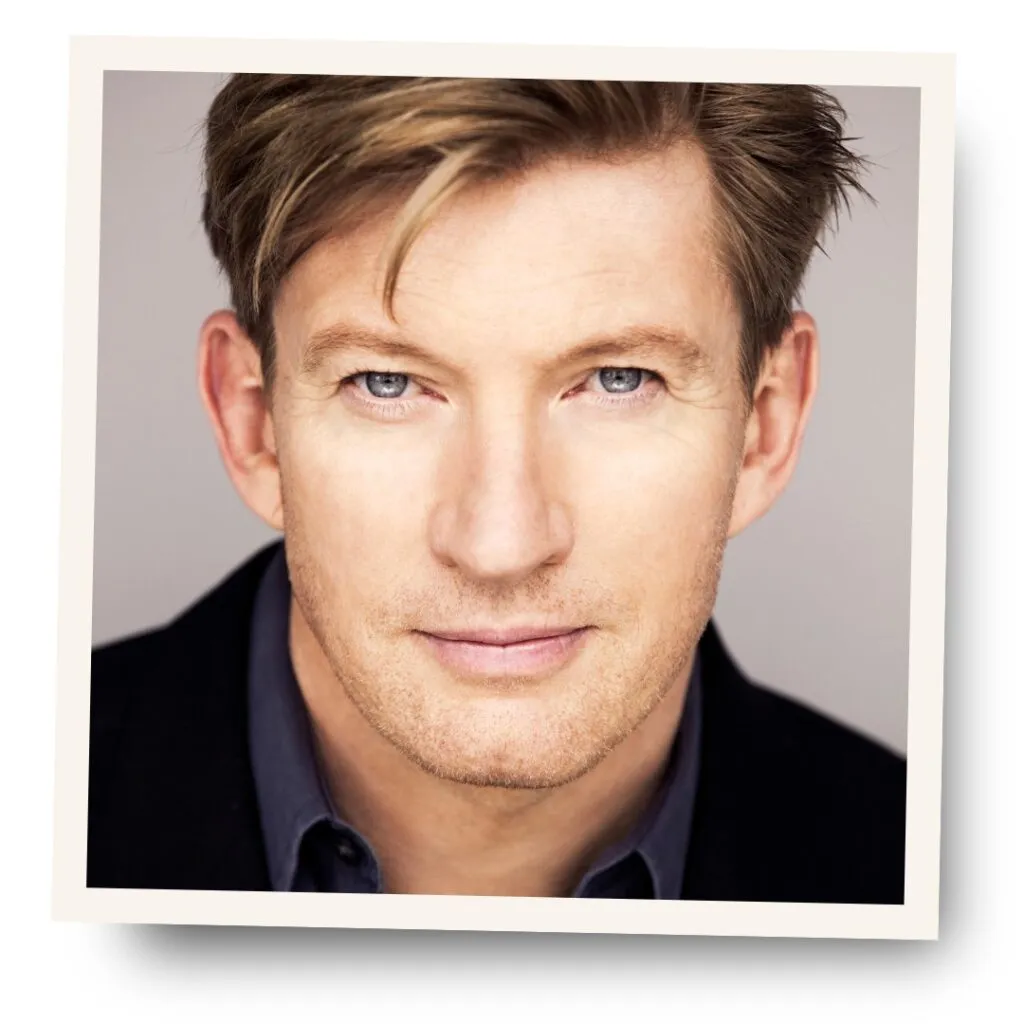

Australian-born Actor David Wenham has long been celebrated as a versatile artist, with captivating performances across film, television, and theatre. Wenham has held an iconic role as Faramir in The Lord of the Rings and interpreted significant roles in the movies 300 and Van Helsing. He even played Hank Snow Baz Luhrman’s Hollywood hit, Elvis.

And in the land of his birth, Wenham is still remembered for playing Daniel ‘Diver Dan’ Della Bosca on the popular TV show SeaChange in the late 1990s.

So why is one of Wenham’s lesser-known roles – as Father Damian in Molokai– still spurring him to action today?

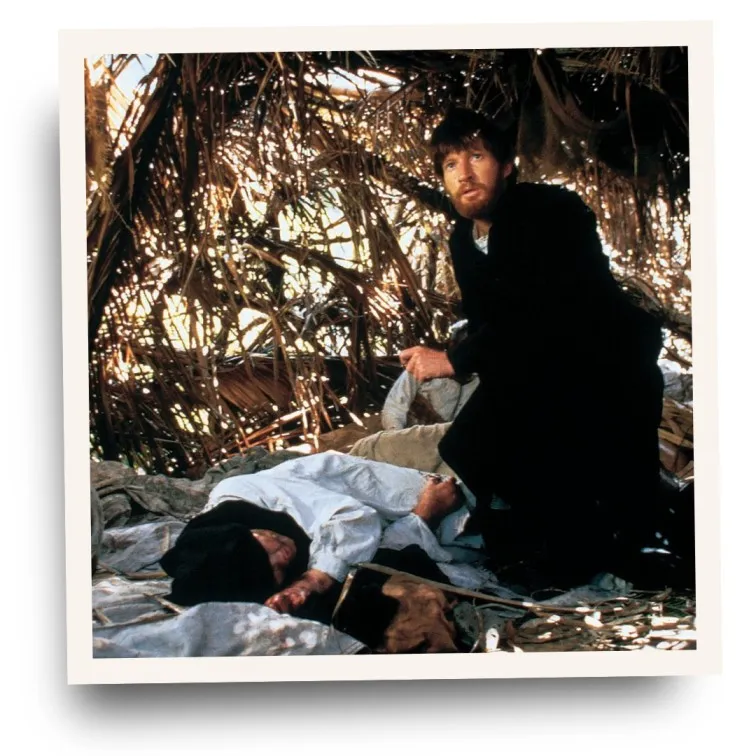

“It’s the story of a Belgian priest, Damien, who volunteered to go to Molokai, an island in Hawaii, in the 19th century and work with leprosy patients. At the time, anybody who was even suspected of having leprosy was sent to Molokai, essentially to rot and to die,” Wenham told a TED X audience in 2019.

“But Damien volunteered to go to Molokai. He went and he built the people houses. He constructed a sewage system. He organised schools. He taught music. And because of him, that community became a place to live rather than to die.”

After sixteen years of serving the isolated leper colony in atrocious conditions on the Hawaiian island, Father Damian himself died from leprosy.

By 1999, when the film was shot, the government had long stopped sending sufferers of leprosy to Molokai. Yet there were still 55 people suffering from leprosy who referred to themselves as “patients” who had chosen to continue living there. Wenham and the film’s director, Paul Cox, lived in their community for five months.

“Until that point, cameras of any description had been banned in the community. But Paul slowly started to gain the people’s confidence, and one by one, the patients came to Paul and offered to put themselves on screen in the film so people could see what this horrendous disease does to a body and a face,” Wenham told his TED audience.

“And Paul tweaked the writing of many of the scenes. So I, as Father Damien, was working with these people and acting and reacting to people who had truly lived the same story we were telling.”

A year after the film was completed, the pair returned to Molokai to show the movie to the patients. Finding nowhere physically in the community to hold a screening, they arranged for each patient to be flown to the “topside of the island,” with two small aircraft making several trips. Each patient was assisted or carried on and off the plane at either end of the short flight until all were settled in a community hall where a makeshift screen had been erected.

Wenham says these people hadn’t seen themselves in a photograph before, let alone on a big screen.

“Yet here they were on screen, telling not only their story, but the story of generations before them.”

After the screening, there were many tears.

“Some [were] tears of sadness, but overwhelmingly, they were tears of pride and joy. They were proud to have been involved in telling such an important story of their history and their culture, and I felt privileged to have been part of their storytelling.”

It is the storytelling, Wenham told his TED listeners, that is why he is an actor.

“Stories can change us. Stories can change our outlook,” he said.

Twenty-five years later, the people of Molokai are still on Wenham’s mind, inspiring him to become a spokesperson for the work that The Leprosy Mission Australia is doing to end leprosy.

“I defy anybody to go to that place and not be affected or moved or changed. These are people who have suffered through the most incredibly disturbing lives and yet are so full of joy and full of life.

“You realise how ridiculous some of the petty things that upset us in our rather privileged lives are. It was a huge life lesson. Those people had a profound effect on me,” Wenham told Brisbane News Magazine in 2003.

He’s also heartened by the progress that has been made, which makes ending leprosy forever a realistic goal.

“Significant achievements have been made. New tools have been developed. We’re now closer to ending leprosy transmission than ever before,” Wenham says.

“Forty-eight hours after a patient starts treatment, they’re no longer contagious. If diagnosed and treated early, permanent nerve damage, disfigurement, and disability are less likely to result,” he continues.

“We can all help end the suffering, restoring lives and communities.”