A journey into the Louisiana community shaped by fear, resilience, and the extraordinary humanity that flourished behind its gates.

If you drive long enough along the slow curves of the Mississippi River, past cane fields that shimmer beneath the heat and groves of cypress trees bearded in their hanging green, you eventually reach somewhere that feels caught between eras. Carville. Quiet, low-lying, and humid in that uniquely Southern way that makes the air feel full-bodied, as though you could hold it in your hand. The kind of place whose silence is made of stories.

Before the site was Carville, it was the Indian Camp Plantation, a sprawling estate that faltered after the Civil War and sank into neglect. Its main house sagged in the weather, its outbuildings slowly surrendered to vine and vine again. Decades later, when Louisiana officials sought an isolated site to house people affected by leprosy, the plantation’s isolation—and abandonment—seemed convenient.

In the 1890s, seven people were taken there under the cover of darkness, ferried upriver on a barge so that locals wouldn’t see them arrive. That hidden journey, performed in secrecy for the comfort of others, set the tone for what Carville would become: a deeply human community built atop generations of misunderstanding and fear.

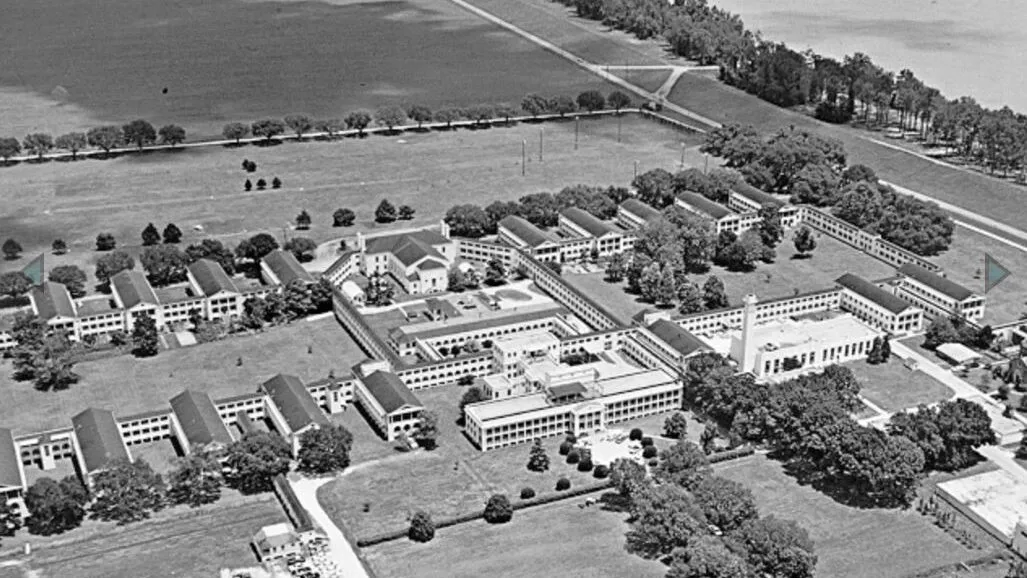

Over the following decades, the site expanded. By the 1920s, the federal government had purchased the property and taken full control. Carville grew into a proper settlement, not a temporary holding place. It would eventually house more than 400 people—an entire town behind a gate.

Civil liberties were compromised from the moment a person entered. Residents could not vote. They were discouraged, often urgently, from using their real names. “For your family’s sake,” staff said. “You don’t want this to follow them.”

They also could not freely leave.

And so many became someone else: a new surname chosen, a first name altered, their arrival sweeping them into a future life both protected and erased.

Despite all the restrictions, Carville became a melting pot of remarkable diversity. Cajun families, African American residents, Filipino workers, European migrants, people from bayou towns and faraway cities—backgrounds braided together not by choice, but by circumstance. The resulting culture, however, was vibrant. This was a place where people with radically different histories cooked each other’s foods, learned each other’s languages, and celebrated new holidays.

It was a life apart from the world, yet deeply connected within itself. There were integrated dances even as segregation still dictated life outside the gate. There were Mardi Gras parades, theatre productions, and a baseball team that was so good that many local clubs wanted to play them.

But Carville’s team never travelled. All games were home games. Leaving wasn’t part of the arrangement.

The daily rhythm of Carville included its own bakery, barbershop, canteen, post office, tailor, and library. Covered walkways were built so residents and staff could stay dry crossing the grounds when Louisiana storms burst open in the afternoons. The atmosphere was subtropical and enveloping, the air warm and weighted with the river’s nearness.

One of the most remarkable truths about Carville is one that counters a century of public fear: not a single staff member ever contracted leprosy during the site’s entire operation. The science was always clear: the disease was not easily spread, and the fear surrounding it was unjustified.

The outside world, meanwhile, held on to its misconceptions with a stubborn grip. One story speaks of a young mother in a small Louisiana town who visited her local doctor for a simple rash. Within hours, she was taken away. Her husband returned from work to find no dinner, four children crying, and no explanation. He went to the sheriff to ask what had happened to his wife. He never saw her again.

The cruelty was not in the disease, but in the fear that normalised secrecy, separation, and lifelong erasure.

Inside the gates, life was often gentler, even hopeful. People fell in love. Carville officials discouraged weddings—and certainly didn’t facilitate them. So, some couples did what couples have always done under pressure: they found loopholes. In the quietest hours of the night, they slipped through holes cut in the fence, crossed onto the other side just long enough to marry at a local courthouse, then returned to Carville as husband and wife. Their vows stood in the eyes of the law, even if they weren’t celebrated within the institution.

Others became advocates. The most influential was Stanley Stein, who eventually lost his sight to complications of the disease but never his determination. He founded The STAR, a publication written, edited, and printed inside the settlement. Through it, he challenged myths, educated the public, and demanded dignity for people who had long been spoken about but whose voices were never heard. The paper went out to thousands of readers; its impact was national.

The museum is housed in a meticulously curated 4,000-square-foot space that breathes life into the stories most powerfully. This is not a place that exploits suffering; it is a place that honours humanity. It is deeply educational, yet not clinical; emotional yet not theatrical.

Inside, you’ll find personal letters, monogrammed suitcases, medical devices, photographs of dances and sporting events, copies of The STAR, hand-drawn illustrations, carefully preserved clothing, and oral histories that are startlingly intimate. You can tour the grounds and view its cottages, communal buildings, and the old dining hall. A nine-stop driving tour leads you through the historic district, narrated by the voices of former residents, drawing us into their memories.

For many visitors, the most moving part is the cemetery. Its lawn is wide and peaceful, bordered by trees and touched by a soft quiet that feels almost protective. Some markers bear real names; others carry the assumed identities residents adopted to shield their families from shame—a reminder of how stigma can rewrite a life, and how remembrance can restore it.

One of the museum’s great strengths is its attention to the daily details: the baseball rivalries, the improvised recipes, the small businesses residents ran, the relationships that crossed cultures long before the outside world was ready to. Stories of holidays, family visits, hidden wedding rings, Christmas performances, and the unmistakable sound of typewriters clacking in The STAR’s tiny newsroom.

Visitors leave Carville with an unusual mix of emotions: sorrow, admiration, tenderness, and more than anything—respect. There is a quiet insistence here that human dignity does not disappear under restriction. It persists. It adapts. It insists on being recognised.

The first question Carville asks us to understand is, ‘What happens when fear is allowed to govern policy?’

The next is an even deeper ask: ‘How can we face the beauty that emerges from people forced to live with the consequences of our fear?’

For anyone travelling through Louisiana, with an interest in history, medicine, civil rights, or even simply curious about the resilience of ordinary people, the museum is worth the journey. It is one of the most significant, most humane historical sites a person can visit, filled with stories that linger long after you leave.

Carville does not ask for sympathy. It asks for understanding. And it gives back far more than it takes.

For more stories like this, you can browse our full collection here!