Imagine having to suffer from a gaping, festering ulcer on your foot for 15 years. A wound that became so infected that the smell drove people away and you had to flee your home. That’s what happened to Nepalese mother, Laxmi. When she first noticed the ulcer on her right foot, she ignored it. It wasn’t painful and she was busy caring for a six-month-old son and a six-year-old daughter. It never occurred to her that the ulcer was a result of leprosy – which left undiagnosed causes peripheral nerve damage and loss of sensation.

However, as Laxmi’s foot ulcer grew, it became infested with maggots. She finally sought medical treatment at Anandaban Leprosy Hospital in Kathmandu and was cured of leprosy.

After completing 12 months of Multi Bacillary-Multi Drug Therapy (MB-MDT) at Anandaban Hospital, Laxmi’s foot ulcer eventually healed, and she returned to her village. However, despite the training in self-care she received at the hospital, she did not practise it at home and walked barefoot. Soon, the ulcer recurred at the same spot. Even more distressing, the ulcer emitted a foul smell, and her neighbours avoided her and her family. So, the family left their home and moved to Kathmandu, where they had no relatives or friends. They found shelter in an informal settlement.

In the 15 years since they left their village, Laxmi has been unable to work properly because of the non-healing ulcer on her foot. Despite 20 visits to Anandaban Hospital for ulcer treatment to receive daily saline dressings, the ulcer showed no improvement. But a miracle was about to occur. Laxmi became the first patient to receive an innovative treatment developed by Dr Indra Napit, the hospital’s senior surgeon and head of research for The Leprosy Mission Nepal.

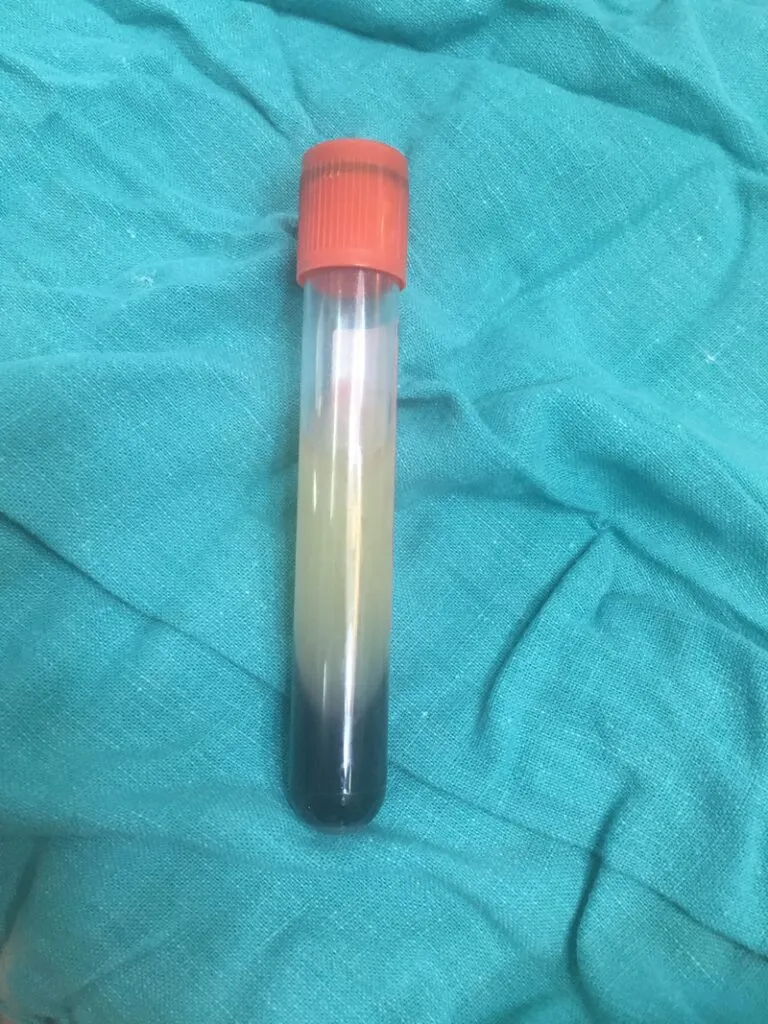

Factors aid skin and tissue growth in the blood. If you take blood, let it settle, and spin it down to remove the red cells, a gel forms in the serum. This gel contains some of these growth factors along with platelets. The gel is known as Leukocytes and Platelet-Rich Fibrin (L-PRF).

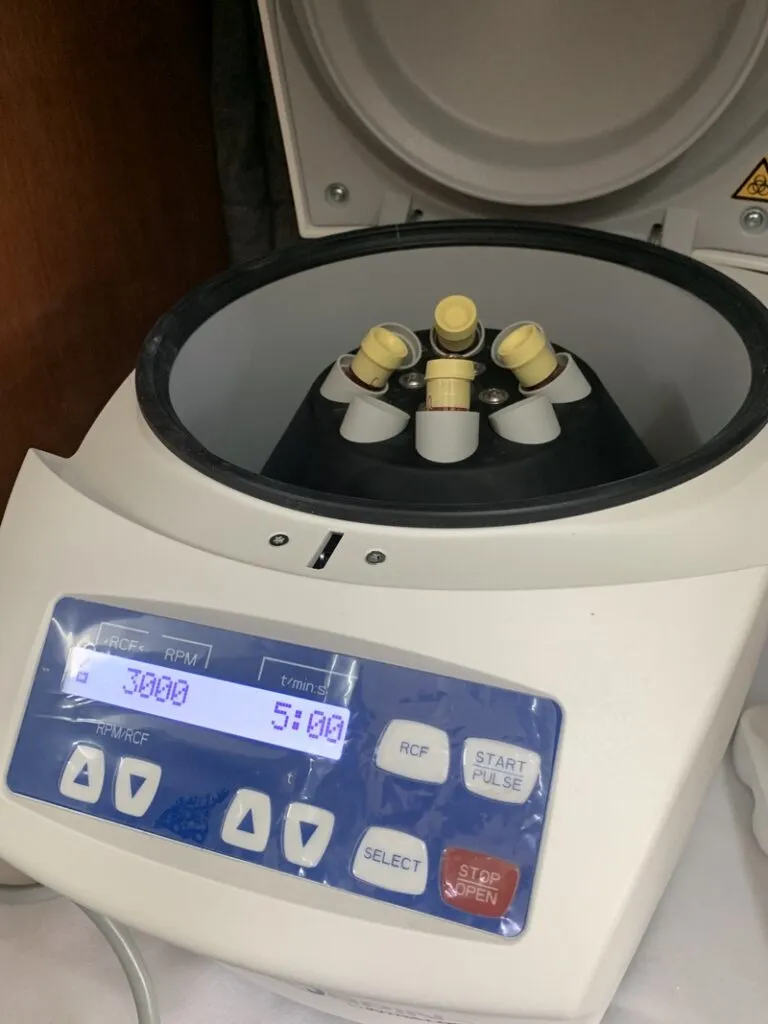

Doctors took a sample of Laxmi’s blood, spun it in a centrifuge to extract the plasma and red cells, and allowed it to clot before flattening it into a thin “patch.” This was then applied to the surface of the ulcer. Staff bandaged her foot, and the process was repeated weekly.

When Laxmi received her first L-PRF application, the ulcer measured 5.8 cm by 2.3 cm and was 1.2 cm deep. At first, it seemed little had changed. However, after the fourth L-PRF application, there was a dramatic improvement. Finally, after six applications, Laxmi’s ulcer was completely healed!

Laxmi was overjoyed to be fully healed and able to work again. She is now practising self-care at home and wearing protective footwear.

Dr Indra Napit pioneered this new treatment and says it meets a great need. He says 50 to 90 percent of Anandaban Hospital’s beds are occupied by patients with leprosy-related ulcers – some for the first time, others many years after being technically cured of the disease, like Laxmi.

“If left untreated, leprosy causes nerve damage. As a result, people affected by leprosy have frequent hospital stays to cure ulcers, which can take many months or even years to heal. However, even the most severe ulcers can heal far quicker with L-PRF. This can prevent disability and even amputation,” says Dr Indra, who completed a PhD in the pioneering treatment.

Cases like Laxmi’s highlight the need for research into effective ulcer treatments, not only for leprosy but also for those associated with diabetes and conditions such as Buruli ulcers and bed sores in elderly hospital patients.

“When I heard about this technique, I immediately thought of its use in leprosy foot ulcers and wanted to try it to see if it works. We performed a pilot study in 2019 and found good results,” Dr Indra explains.

“It took a few months to establish it well for use in leprosy foot ulcers as it was not tested properly in leprosy before. We started this in Anandaban in January 2018. It has already been implemented in many other hospitals in Nepal and a few other countries, such as Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia. We have already conducted two national and one international workshop on this new technique.”

The good results from this innovative technique helped Anandaban hospital gain funding for a randomised controlled clinical trial from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) UK. The study started in December 2019 and was completed in November 2023, with the findings published in May 2024 in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases journal. The trial showed that L-PRF was better than standard treatment with normal saline dressing, but the effectiveness was not significant enough to justify regular use in practice.

“So, we need to do a bigger study – if possible, a multi-centre/multi-country study. The trial was conducted during the COVID pandemic, so we think the result is affected by it as many patients enrolled in the study had foot ulcers with prolonged duration of ulcers.”

Professor Warwick Britton, Director of Research for Sydney Local Health District and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, observed the treatment at Anandaban Hospital when it first began.

“I’ve seen it used and it definitely is a benefit to some patients,” said Professor Britton, who has a longstanding research interest in the control of tuberculosis and leprosy in high-burden countries.

“It is a significant development, and one of the reasons is that this is something that can be readily applied anywhere. It’s a simple approach using the healing properties of plasma in a very cost-effective way,” he says.

He suggests that it could be used in Australia to help older people who often develop a wound during a long stay in hospital after a stroke, for example. “This is actually a major health problem because it causes severe discomfort and contributes to a functional decline in people. This is a major cost to the whole health system, and the work in Nepal could be a practical approach to this problem.”

.