Commemorating over 150 years since the discovery of the Leprosy Bacillus, Jenny Davis shares her experience of two labs...

This is a story of two laboratories – separated in time by more than a century and in space by thousands of kilometers – and it’s about what I learnt as I visited them.

Bergen in Norway – ‘the heart of the fjords’ – is renowned for its scenery and history. But the attractions for me in 2006 were hidden rooms up a flight of stairs, in ‘The Secret Laboratory’ at the University of Bergen Department of Public Health and Primary Health Care. This was where Dr Amauer Hansen worked in the late 19th century and the rooms and their contents have been preserved intact since then. Here I was – walking back in microbiological history!

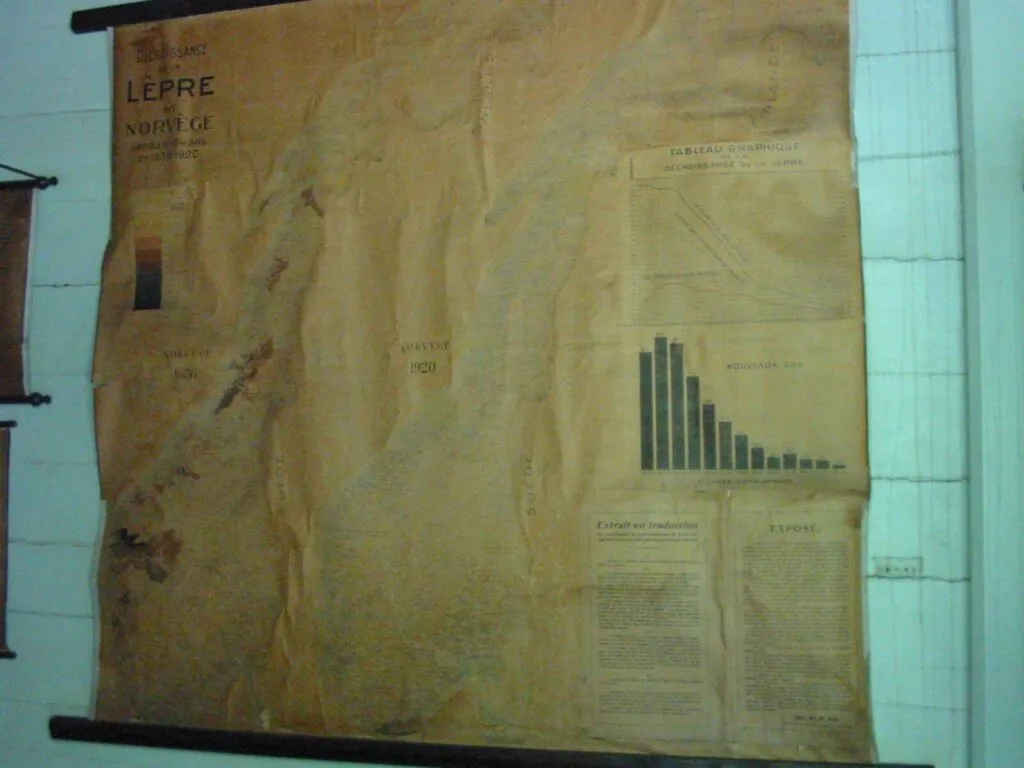

Just outside the lab was an old chart with statistics for leprosy, then a major health problem in Norway. The young doctor Amauer Hansen had made it his task to study leprosy. Against the current theories at the time, he concluded from evidence in the Leprosy Registry that the disease was infectious (passed from person to person) and not hereditary (passed from parent to child).

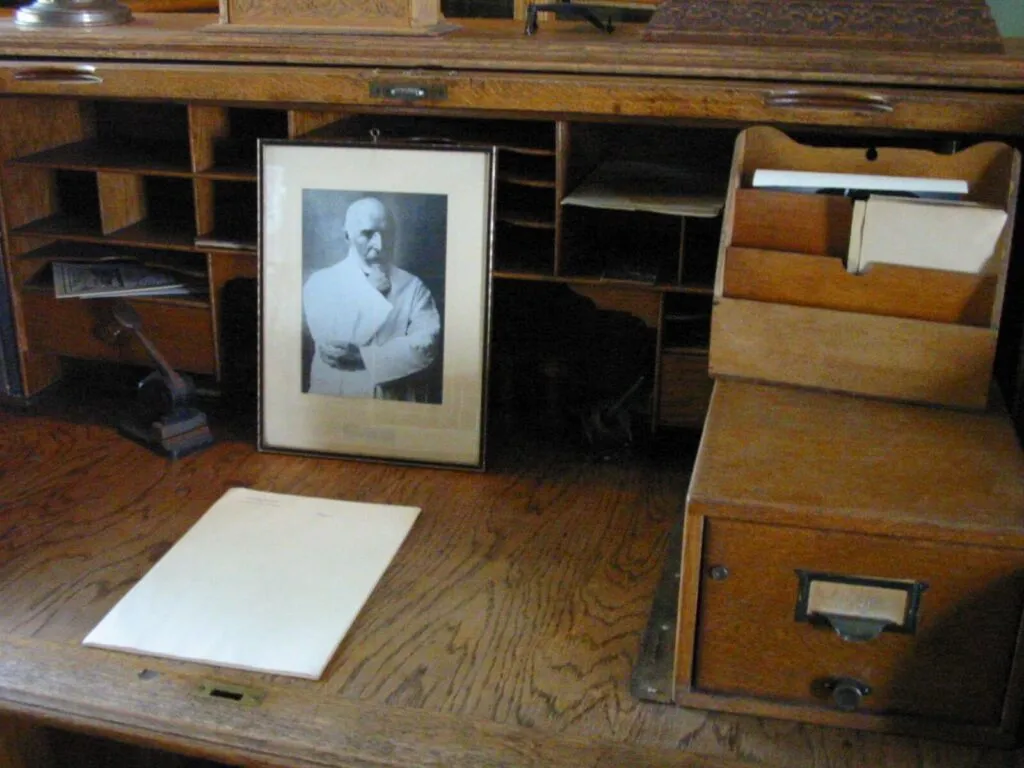

As a microbiologist with a keen interest in history, I was fascinated to see the laboratory and office occupied by this scientific pioneer. Entering the laboratory area, I could see familiar objects – workbench, shelves of chemicals and the insulated chamber for incubating cultures. And there was my favourite piece of equipment, an old-fashioned brass microscope, so different from today’s models, but still enabling the scientist to view tiny bacteria.

Hansen used a microscope to observe ‘rod shaped bodies’ in tissue from a patient in 1873, and published his findings in 1874. Although it was some years before he could confirm these ‘bodies’ as bacteria, this was a major finding! Hansen is recognised as the first person to associate that bacterium – Mycobacterium leprae – with leprosy. Leprosy’s name ‘Hansen’s Disease’ honours that discovery.

Through a doorway from the laboratory was Hansen’s office, with its imposing roll-top desk, a glass-fronted book-case and impressive collection of pathology specimens and wax casts. It was in this setting – dark and uninviting compared with today’s offices – that Hansen worked through the complex issues of leprosy research in his time.

Looking around, I reflected on the persistence and curiosity of this doctor who changed the way people thought about leprosy and spent his professional life seeking its causes.

You can read more of Hansen’s story here and take a virtual tour around his laboratory here

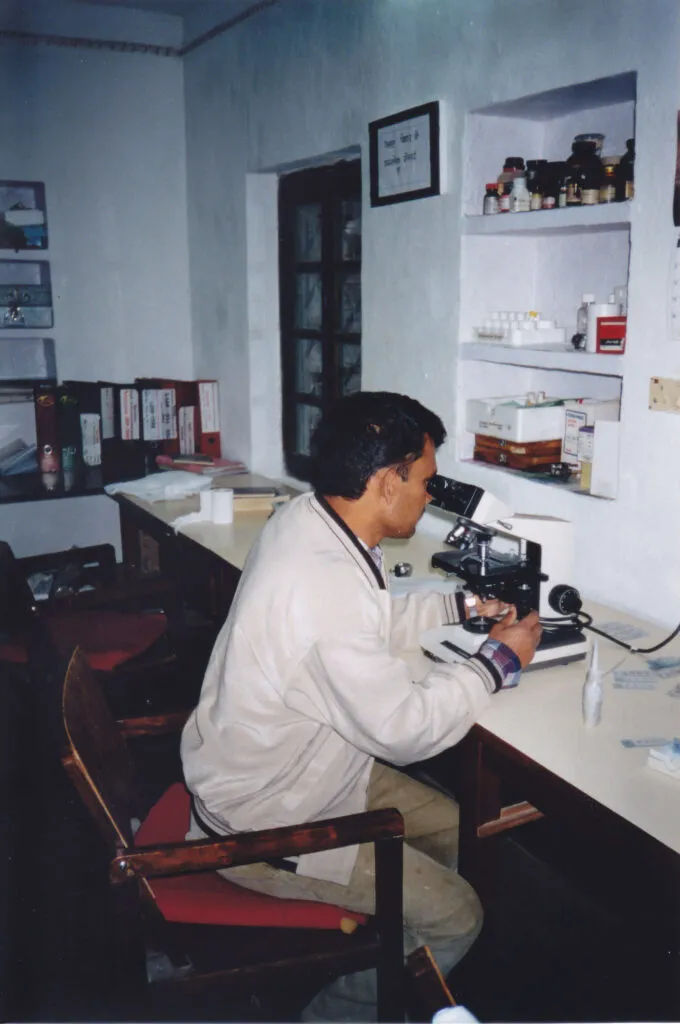

Moving forward a century and over nine thousand kilometers, I visited scientists in a second laboratory. Like Hansen, they also sought to unlock problems and work for the benefit of people affected by leprosy. I had the opportunity in 1999 to visit the Mycobacterial Research Laboratory (MRL) at Anandaban, set in the ‘Forest of Joy’, about 12 kilometers from Kathmandu, capital of Nepal. Like Norway, Nepal has magnificent scenery – and also like Norway in the 19th century, it still faces leprosy as a disease of poverty. As I travelled on the bumpy road from Kathmandu and saw the obvious signs of poverty, I wondered whether research scientists could make a contribution. Weren’t there more urgent needs?

Anandaban Hospital is a leprosy referral hospital – so, like Amauer Hansen, laboratory scientists here are in daily contact with leprosy patients and their clinical care. As I negotiated the steep slopes and admired the spectacular views around the complex, I met some of these patients, with the medical and paramedical staff. But, the laboratory was my focus. So with an enlarged view of what’s involved in wholistic care for a person with leprosy, I headed up the track.

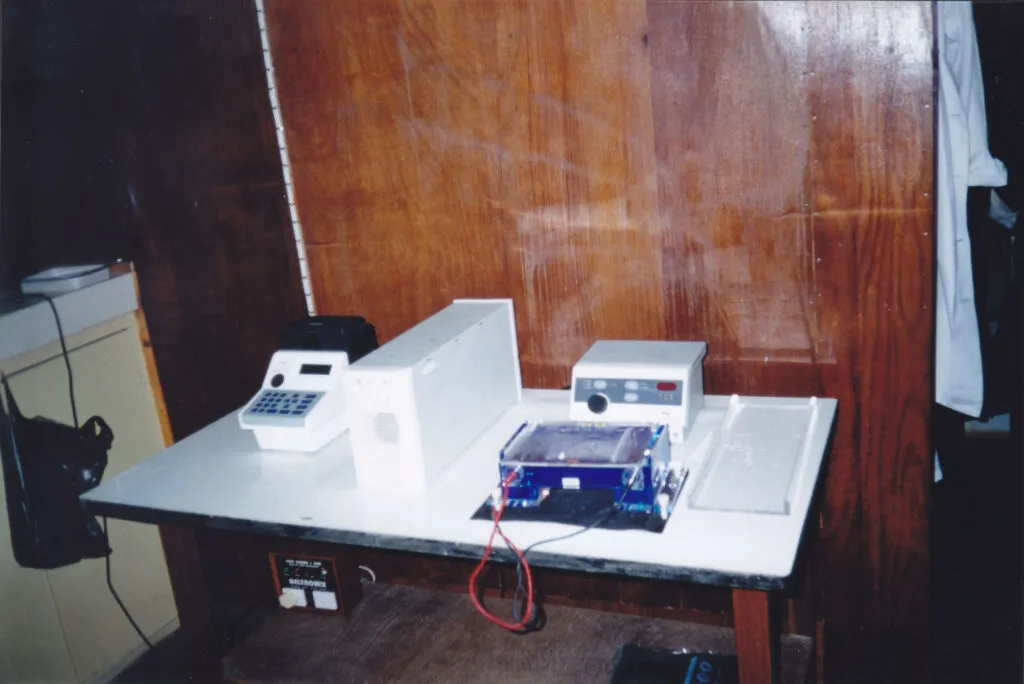

Soon I was in the Mycobacterial Research Laboratory, swapping stories with other microbiologists and looking down a microscope at Mycobacterium leprae – my first view! I was impressed by the scientific skills of the staff, who detected the bacterium in skin tissue and determined its antibiotic sensitivity with basic tests.

But even more exciting was the application of cutting-edge techniques and the research into this complex disease. How can we measure someone’s exposure to leprosy? How can we tell if the antibiotics are still effective? Can we find the best treatment for a ‘leprosy reaction’ ? The answers to these questions were being explored.

Since the COVID pandemic, most of us recognize terms such as ‘PCR’ and ‘genetic testing’. But at the time of my visit in 1999, these were part of a relatively new technology. As I spoke with the scientists using these methods, saw their equipment and heard of their collaborations with other laboratories, I was really encouraged.

So I had an answer to my question ‘What can scientific research offer to Nepal?’. Although direct benefits were not always immediately applicable to individual patients, the work at the Mycobacterial Research Laboratory was contributing to the bigger picture and helping to provide better ways to fight this ancient disease.

You can read my full account of the visit here and learn more about MRL today here.

Two laboratories, and scientists working with curiosity, skills and persistence, showed me how microbiology in the 19th and 20th centuries has been part of the journey towards ‘Triple Zero’ in the 21st century.

Jenny Davis is a microbiologist, a Life Member and former Board Chair of The Leprosy Mission Australia.