As an ancient disease, the word ‘leprosy’ comes with a whole lot of metaphorical baggage.

On the one hand, many of us are overly familiar with leprosy. We don’t respond to leprosy like we might to ‘diverticulitis’ or something less familiar. Nobody says, “I have no idea what that is”, or pulls out Dr Google. People generally feel like they know what leprosy is.

Unfortunately, what people ‘know’ about leprosy is often incorrect.

“Leprosy is super contagious if you touch it, right?” Um, no. It isn’t, and it isn’t. “It’s like a skin disease that eats away the flesh, yeah?” No. It’s just not.

How we ended up here—where people are both overly familiar with leprosy and often misinformed—is a whole other question.

Common knowledge about leprosy somehow became locked down a long time ago—it is an ancient disease, after all—and never seems to have been updated, even when medical understandings and treatments have gone ahead in leaps and bounds.

Somehow, our curiosity about leprosy remains satiated by old information, and we don’t even realise what we don’t know. Once we do start learning a little bit about leprosy, though, our curiosity is quickly re-awakened.

The basics

Leprosy Transmission

First, you learn that you can’t catch leprosy touching someone who has it. Nor by hugging them or sitting next to them. You can’t even catch leprosy by having sex with someone. Pregnant mums do not pass leprosy on to their children.

In most cases of leprosy transmission, close intimate contact for a prolonged period (perhaps even years) needs to happen. Respiratory transmission is a possibility, though it remains poorly understood and rare.

New medical research even suggests that not everyone exposed to prolonged intimate contact will contract it. Most people (estimated 85–95%) have natural immunity to leprosy, meaning only a small percentage of those exposed actually develop the disease. So, while leprosy has a reputation for being super contagious and easily transmitted, it’s the complete opposite.

Incubation

Leprosy is caused by one of two bacteria: Mycobacterium leprae (common) and Mycobacterium lepromatosis (rare). This article will focus on Mycobacterium leprae.

One of the most important things to know about Mycobacterium leprae is that it replicates incredibly slowly. So, while E.Coli bacteria replicates every 20 minutes, Mycobacterium leprae replicates once every one to two weeks or so.

That means leprosy’s incubation period (i.e. the time between exposure to the bacteria and the first appearance of symptoms or signs of illness) can be anywhere from six months to twenty years.

All of this presents challenges in leprosy diagnosis and treatment. Someone with a disease exhibiting no symptoms is unlikely to be diagnosed and treated—a significant obstacle when working towards zero transmission.

But even more challenging is the treatment required. Many classes of antibiotics target bacteria as they are replicating. So, non-replicating bacterium is resistant to several classes of antibiotics.

This means leprosy patients must take a cocktail of antibiotics over an extended period, allowing the right antibiotic to target the bacteria when replicating while ensuring multiple drugs are used so the patient doesn’t become resistant to the treatment. The standard treatment for leprosy is Multi-Drug Therapy (MDT), which includes the drugs dapsone, rifampicin, and clofazimine. This combination prevents antibiotic resistance and has been key to reducing global leprosy cases.

Symptoms

A simple definition of leprosy is this:

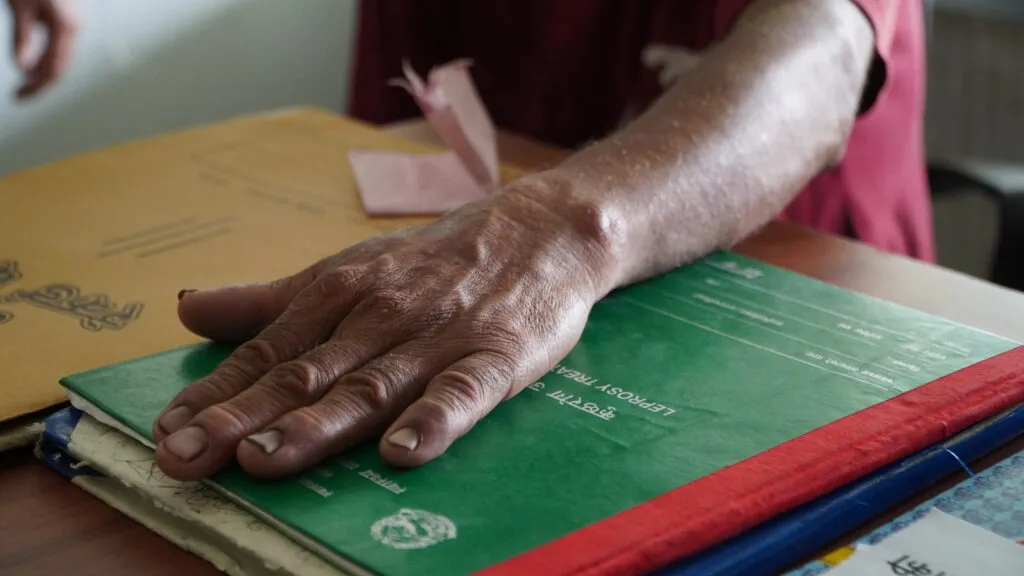

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease that affects the skin, peripheral nervous system, eyes and upper respiratory tract. Untreated leprosy can lead to progressive and permanent disabilities.

While robust, that definition doesn’t do justice to describing the myriad of symptoms a person affected by leprosy can experience—another area where misinformation abounds.

Leprosy’s symptoms are:

- Discoloured, pink or pale patches on the skin;

- Painless ulcers on the soles of the feet;

- Nose bleeds and nasal congestion;

- Painless swollen lumps on the skin of the face and ears;

- Thickened, stiff and dry skin; and

- The loss of eyebrows and eyelashes.

Leprosy symptoms caused by nerve damage are:

- Enlarged nerves around the elbows, knees and side of the neck;

- Numbness in patches of skin;

- Eye problems; and

- Muscle weakness and paralysis, especially in hands and feet.

Left untreated, these symptoms can progress to:

- Crippling of the hands and feet;

- Chronic ulcers on the soles of the feet that do not heal;

- Blindness;

- Nose disfigurement;

- Fingers shorten because of loss of sensation, multiple traumatic events and bone weakening and reabsorption due to nerve damage.

- Pain and tenderness in nerves;

- Pain and redness of the skin; and

- A burning sensation of the skin.

Deeper dive for the curious—and the compassionate

Before continuing with this article, it’s important to note that this author is not a medical professional.

But she does have a healthy curiosity and a beating heart. Hence, she recently went down the rabbit hole of medical research to try to learn more about what’s happening in the body when a person contracts leprosy. (How does a disease cause a person to exhibit so many completely different symptoms?)

That said, rest assured that this article has been checked by a medical professional who understands leprosy and diligently corrected all the author’s mistakes before you begin reading it.

Let’s go.

The Peripheral Nervous System

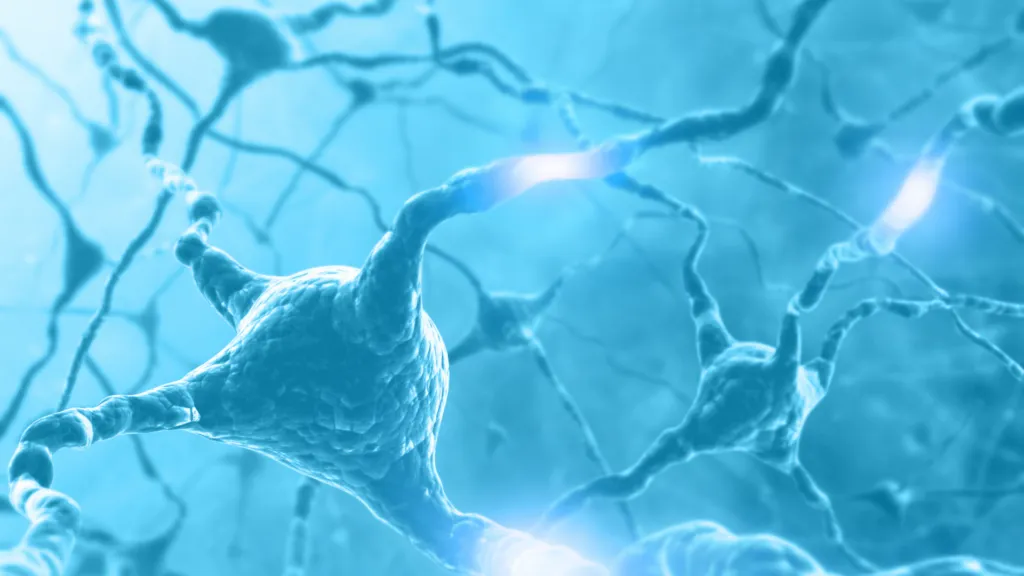

The peripheral nervous system is an extensive communications network that transmits electrons (i.e. sends signals) between the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) and all other body parts. It consists of bundles of fibres made up of nerves (the main component), ganglia and nerve plexuses.

There are two parts to the peripheral nervous system: the somatic system and the visceral nervous system. The somatic system is responsible for input and output related to skeletal muscles, bones, joints and skin. The visceral nervous system is responsible for innervation of smooth muscle, cardiac muscle and glandular cells.

Peripheral nerves play a crucial role in transmitting sensory information to the brain, such as the sensation of cold in your feet. They also relay signals from the brain and spinal cord to different body parts. These nerves communicate with muscles, instructing them to contract for movement, while also regulating vital functions like heart rate, blood circulation, digestion, urination, sexual function, bone health, and immune responses. When peripheral nerves fail to transmit signals properly, it can lead to significant health issues throughout the body.

Peripheral Neuropathy

The term peripheral neuropathy is an umbrella term used to describe various conditions that result in damage to the peripheral nervous system, such as leprosy. Peripheral comes from the Greek term meaning “around” and refers to being outside or away from the central nervous system. Neuropathy is derived from two ancient Greek words: “neuro” (meaning “nerve”) and “pathos” (meaning “affliction” or “condition”).

Peripheral neuropathy describes when a patient’s nerve signalling has been disrupted in one of these three ways:

- Signals that should be sent, aren’t being sent.

- Signals are being sent, when they shouldn’t be.

- Errors in the body are resulting in the messages that are being sent being changed.

While some forms of peripheral neuropathy affect only one or a few nerves, in most cases, many or most of a person’s nerves are affected.

There are over 100 recognised types of peripheral neuropathy, each with distinct symptoms and patterns of progression. The specific symptoms depend on which type of nerves—motor, sensory, or autonomic—are affected.

- Motor nerves regulate voluntary muscle movements, such as walking, grasping objects, and speaking.

- Sensory nerves relay information about touch, temperature, and pain, such as feeling a light touch or a cut.

- Autonomic nerves manage involuntary functions like breathing, digestion, heartbeat, and gland activity.

Many neuropathies involve all three nerve types to different extents, while some primarily impact one or two. Doctors classify these as motor neuropathy, sensory neuropathy, sensory-motor neuropathy, or autonomic neuropathy, depending on the specific nerves involved.

Most cases of neuropathy are length-dependent, meaning symptoms typically start in the feet—the nerves farthest from the brain—and may worsen or spread upward over time. In more severe cases, symptoms can progress toward the body’s centre. However, in non-length-dependent neuropathies, symptoms may first appear around the torso or in various locations without a clear pattern. Leprosy is one of the most common causes of nontraumatic (not caused by a physical trauma such as an accident or assault) peripheral neuropathy in the developing world.

Leprosy’s impact on the peripheral nervous system at a cellular level

Neurons are the cells of the nervous system that carry information throughout the body—and there are around 86 billion of them. Most neurons contain these five features: the dendrites, cell body, axon, myelin sheath, and axon terminals.

Dendrites—wrench-like extensions—often extend from the cell body. These can receive information being passed on by other neurons.

The axon is the conducting part of a neuron. Axons pass on information received by dendrites, usually to another neuron. Some neurons are wrapped in a fatty coating called myelin sheath, which helps increase the conduction of the electrical signal down the axon.

Myelin is created by Schwann cells (the process is called myelination). Hence, Schwann cells play a critical role in the regeneration of nerve cell axons in the peripheral nervous system.

Mycobacterium leprae has a predilection for Schwann cells and infects them. It causes the myelin (the sheath protecting the axon, where the electrical signal is conducted) to die. It does this by killing the Schwann cells’ mitochondria, which produce energy so it can function.

Over time, the cell’s axons also become damaged by the body’s immune system’s response to the bacteria, secondary inflammatory changes, and destruction of the nerve architecture. A significant portion of nerve damage in leprosy is caused by the body’s immune response to the bacteria, leading to inflammation and further destruction of nerve cells.

Hence, the body’s peripheral nerve system is disrupted by leprosy in specific ways. As explained above concerning all cases of peripheral neuropathy:

- Signals that should be sent, aren’t being sent.

- Signals are being sent, when they shouldn’t be.

- Errors in the body are resulting in the messages that are being sent being changed.

The result is the leprosy symptoms we recognise— from injuries that do not register with pain to muscle weakness and paralysis to nerve pain.