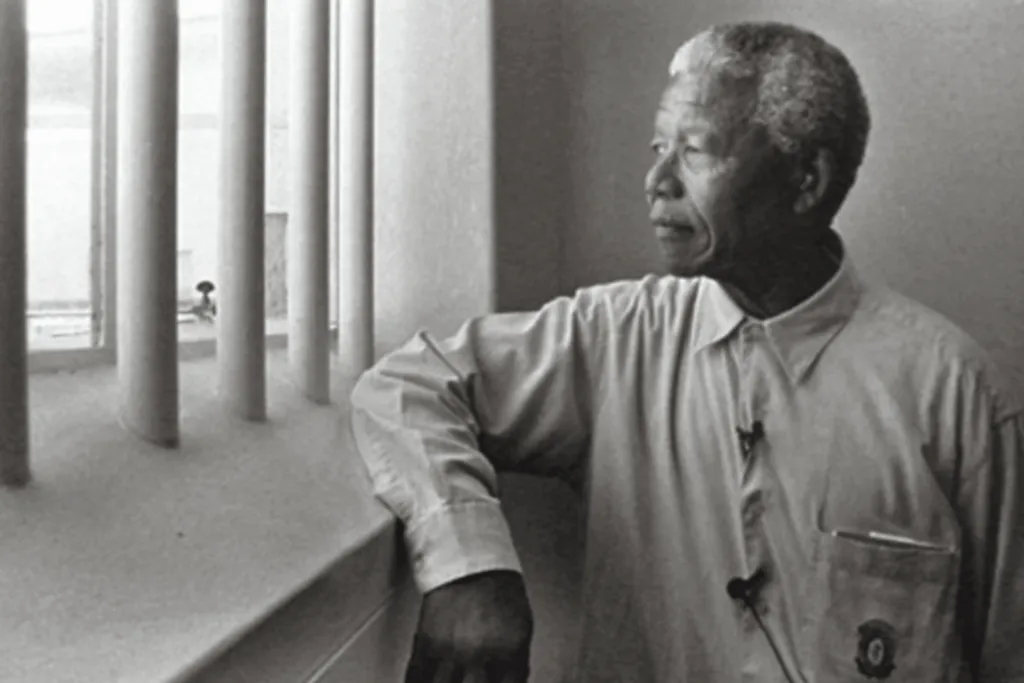

Leprosy stigma—its weight, its legacy, and its consequences—is at the heart of one of Robben Island’s lesser-known histories. On a bright morning, tourists board a ferry in Cape Town, bound for Robben Island. Most of them are there to see Nelson Mandela’s prison cell. To stand in that small space and imagine the weight of injustice. To walk through a place where history pressed so heavily on one man, and by extension, on an entire nation.

But there’s another story that lingers on the island. One that came before the prison and is, in many ways, harder to hear.

For nearly a century, Robben Island was home to hundreds of people affected by leprosy. Men and women, mostly poor, mostly Black, forcibly removed from their homes and shipped across the water. Not because they had committed a crime. But because they were considered untouchable.

From 1846 to 1931, the island functioned as a leprosarium. Under the Leprosy Repression Act of 1891, leprosy wasn’t just a disease to be treated—it became a legal justification for forced isolation. The Act required anyone diagnosed with leprosy to be removed from their community and detained indefinitely, often without consent or the right to appeal. Families were torn apart by law. The language of the legislation was clinical, but the outcome was deeply personal: mandatory segregation, institutionalisation, and in many cases, abandonment.

Many never returned. Some died on the island and were buried in unmarked graves. The records are incomplete. The stigma, overwhelming.

We don’t like to use the word “stigma” much these days. It sounds a bit abstract. But for people affected by leprosy, it meant being separated from your children. It meant being cut off from family and community, and placed in institutions with few rights and little dignity.

And that treatment didn’t end when they stepped off the boat—it was baked into the system.

The Church of the Good Shepherd—designed by Herbert Baker and built in 1895—was one rare exception. A physical gesture of spiritual care, made possible only because Rev. W.V. Watkins, the island’s chaplain at the time, personally financed its construction and purchased the land himself when the colonial authorities refused to allocate any for the church.

According to architectural records, the church was built by the leprosy patients themselves, using stone quarried from the island. The colonial authorities wouldn’t set aside space for a church, so he paid for it himself.

It’s the only privately owned land on the island and still belongs to the Anglican Church of South Africa. To this day, the bell tower is used to raise a pink or blue flag when a new baby is born on the island—a quiet sign of continuity, of life persisting in a place known for exile.

But even that story is incomplete. The church was for male patients only. Women were housed separately in more crowded quarters, their experience even more invisible. In 1893, they staged a protest over their conditions—a rare moment of documented resistance from female patients, whose experiences are otherwise largely absent from the historical record. More at: https://www.robben-island.org.za/resistance-1892-1893/

It’s one of the few things we know about them. Their graves are mostly unmarked, and their names are largely lost.

Still, people come to Robben Island.

They come during their holidays, with cameras slung over their shoulders, wearing sunhats and sneakers. They walk the grounds. They stand in silence. They listen—not just to Mandela’s story, but to the layered history of the place. The pain, yes—but also the resilience. The quiet endurance of dignity.

A cynic might say it’s voyeurism—that it’s just another form of dark tourism. Maybe, for some, it is. But I think there’s something else going on, too. Something gentler. I think we want to honour the lives that passed through this place. I think we know, deep down, that to remember well is an act of love.

For those of us committed to seeing the end of leprosy, Robben Island isn’t just a historical site. It’s a reminder of what can happen when stigma is written into law—when fear, not evidence, shapes policy, and compassion takes a back seat.

The movement to eliminate leprosy isn’t only medical—it’s moral. It’s about making sure no one is ever exiled again for being unwell.

Today, some of the tours are led by people who were once incarcerated there. Others are led by former guards. They work together now, telling the same story. Not because they agree on everything, but because they agree the truth should be told.

Peacebuilder John Paul Lederach calls this kind of work “moral imagination”—the ability to envision a future rooted in dignity and shaped by empathy.

Robben Island isn’t a fun day out. But it is a meaningful one. It offers something many of us are quietly craving: the chance to look reality in the face and not turn away. The chance to say, “That was wrong. That was unjust. They deserved better.”

So we visit places like Robben Island—even on our holidays. We walk. We listen. And we remember.

Because remembering well might just be one of the most hopeful things we can do.

For more stories like this, you can browse our full collection here!