Oshima. A remote Japanese island tells the story of residents who were cut off from the world—and some who chose never to leave.

They threw it into the sea. It’s a reality that visitors to Oshima are forced to contend with when faced with the cement table standing on a small patch of earth near former dormitories—an apt symbol of the island’s complex history.

“It” is a rectangular slab of cement, scarred by decades of use as an autopsy table for people affected by leprosy. Once the site of forced examinations, this heavy table was a silent witness to the lives of people whose bodies were tightly controlled by law, then dissected, studied, and erased. Its surface is pitted and rough, each imperfection a quiet testament to pain, survival, and memory.

And when the practice of performing autopsies on deceased residents was discontinued, they threw it into the sea.

When artists lifted it from the sea in 2010—encrusted with shells and sea growth—intending to display it during the Setouchi Triennale, the residents of Oshima were divided over the prospect of its display. Some recoiled at the memory, others insisted it be shown. Yet now the table stands, a raw artifact of history, confronting visitors with its presence.

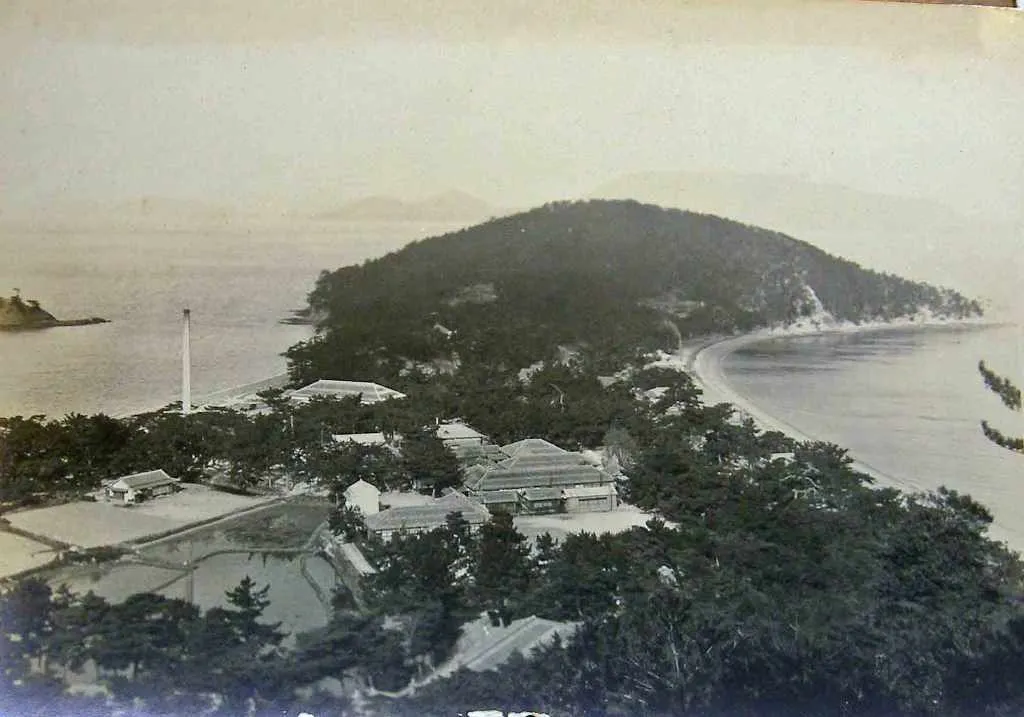

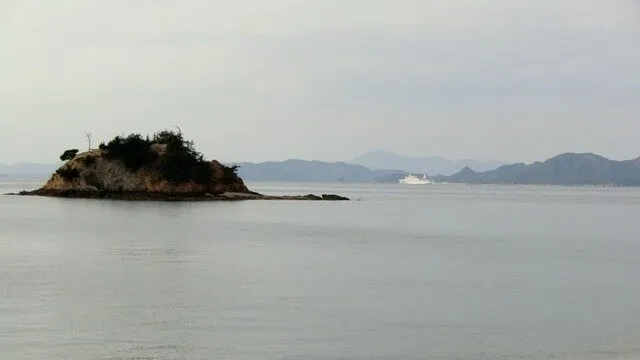

The journey to Oshima from urban Japan is brief, but the transformation is immediate. From Takamatsu City—the capital of Kagawa, Japan’s smallest prefercture—the ferry crosses the Seto Inland Sea in just fifteen minutes. The mainland recedes, a blur of hills and ports fading into mist. The sea stretches like polished steel, and other islands hover like ghostly outlines.

On approach, Oshima appears deceptively calm: whitewashed roofs tucked among low green hills, paths winding gently across the terrain. An island paradise to the unknowing eye. Yet beneath its serenity lies a history of isolation, pain, and enduring human resilience.

The first thing visitors notice are the white stripes painted along the streets, bold guides for residents with impaired vision. Music hums faintly from speakers rigged to trees and lampposts, offering both orientation and reassurance. The streets themselves are empty; no cars intrude, no crowds gather. Silence dominates, punctuated by wind and the occasional distant voice. The faint hum of human presence feels both intimate and ghostly, a reminder that life continues in careful rhythms shaped by decades of confinement.

For nearly a century, Oshima was a prison in the guise of a sanatorium. Beginning with the 1907 Leprosy Prevention Law, enforced and revised through the mid-20th century, people affected by leprosy were removed from their homes and sent here. Families were torn apart, children separated from parents, possessions confiscated, marriages strictly regulated, and personal freedom constrained. Patients were confined for life; healthy people were forbidden to visit. The island, surrounded by the sea, became both refuge and cage, a world apart from the mainland.

The law endured until 1996—long after effective treatment had been available. Most residents were cured decades ago, yet many chose to remain on their island home.

So, Oshima is home now, a place where the past lingers in physical and social space, where memory and choice intersect. Residents live with the consequences of long isolation: limited mobility, impaired vision, and chronic conditions, yet they maintain agency and community in ways both ordinary and extraordinary.

Hence for the discerning traveller, walking through Oshima is walking through memory itself. Dormitories rise along narrow, striped paths, weathered and softened by moss and salt air. Gardens bloom where residents once cultivated vegetables; small courtyards echo with faint music, the constant reminder that life, though constrained, continues. The Memorial Museum houses diaries, photographs, and personal objects: embroidery, letters, tools once used in daily work. Here, the stories of forced isolation coexist with evidence of resilience, creativity, and quiet dignity.

Remarkably, it is art that has become a bridge between the island’s past and its present.

Artists from the Setouchi Triennale convert dormitories into exhibition spaces. Dioramas portray the daily lives of residents, including candid moments of care and hardship. Artists participating have collected local stories, transforming them into experiences that connect generations. The recovered autopsy table, once discarded to the sea, stands in deliberate contrast to these artworks—a reminder that memory and trauma are inseparable from the beauty and life that now persist.

Residents continue to shape the island in tangible ways. They maintain gardens, organise exhibitions, and preserve the stories of those who came before them.

Though their numbers dwindle and most are in their eighties, the residents anchor Oshima in the present, living deliberately amidst the ruins of their once forced seclusion. Every path, every wall, every garden is a testament to endurance, memory, and the quiet assertion of dignity.

The island’s beauty is subtle and unsettling. There is no single vista to dominate the eye. Instead, it reveals itself slowly: sunlight slanting across courtyards, the ferry’s wake tracing long ribbons on steel-blue water, distant hills softened by haze. Visitors feel both the weight of history and the persistence of life. They sense the lives once constrained by law, and the lives that continue, resilient and chosen.

Oshima asks a difficult question that is as relevant today as it has been for millennia: how does one live in exile within one’s own country? And perhaps a second: how can a country exile their own?

Here, the sea is at once barrier and passage, memory and present, isolation and connection. Walking its quiet paths, visitors feel the measured pulse of a community that has survived law, time, and distance—not merely enduring, but shaping a life that insists on its own terms.

The island does not offer spectacle or easy answers. This isn’t the ideal tourist destination for someone looking to escape contemplation and just zone out. Yet it is undeniably worth visiting—and a place that will inevitably enrich the soul of all who dare.

Oshima lingers in the mind: the slope of a garden path, the gentle tilt of sunlight across a courtyard, the hush of wind over empty streets. Its story has endured because its people endure still.

And in their persistence, Oshima becomes something larger than history—a quiet testament to the human capacity to survive, to adapt, and to live with dignity even when the world has tried to deny it.

For more stories like this, you can browse our full collection here!